ACTA ACUSTICA UNITED WITH ACUSTICA というヨーロッパの音響学会誌に、Dr.Clemens Buttner氏が筆頭の、私を含む共著で「The Acoustics of Kabuki Theatres」というテーマでの論文が掲載されました。

内容は、代表的な八つの芝居小屋―明治座、白雲座、内子座、金丸座、鳳凰座、村国座、八千代座、嘉穂劇場―について、ISO3382の室内音響の評価方法に従って空席状態の劇場を測定し、満席状態の音響特性についてシミュレーションを行ったものです。

俳優と観客が共感して一つに融合する劇場空間の無限の自由』があることとしています。芝居小屋の公演内容が音楽を伴う演劇が主のために、音響空間は音声の明瞭性が重要になります。したがって残響時間は約1秒程度で、残響2秒のクラシックコンサートホールが出来るまでずいぶん時間がかかりました。このように日本の芝居小屋とクラシック用のホールでは音響特性は別ものです。

以下、論文を掲載します。日本語部分は藪下による翻訳です。

-----------------------------------------------------------

The Acoustics of Kabuki Theaters

写真:左から:Clemens Buttner氏、藪下 満、森下 有氏、Antonio Sanchez Parejo氏、明治座の館長 加藤周策 氏、Stefan Weinzierl 氏 2017年9月26日かしも明治座前で撮影

(訳者写真追加)

Summary

The study presents a room acoustical investigation of a representative sample of eight Kabuki theaters as the most important public performance venues of pre-modern Japan. Room acoustical parameters according to ISO 3382 were measured for the unoccupied and simulated for the occupied condition. In comparison with European proscenium stage theaters, they have lower room heights in the auditorium, with usually only one upper tier, and no high stage house for movable scenery. The lower volume per seat results in lower reverberation times, The wooden construction and the audience seating arrangement on wooden straw mats on the floor instead of upholstered seats leads to a mostly flat frequency response up to 4 kHz, resulting in an excellent speech intelligibility, as documented by values for definition (D50) and the speech intelligibility index (STI). The acoustical conditions support the dynamic acting space created by pathways extending the stage from the front through the audience to the rear of the auditorium. They allow great contrasts in the perceived acoustical proximity depending on the selected acting position, and support a high degree of immersion of the audience into the dramatic action.

© 2019 The Author(s). Published by S. Hirzel Verlag · EAA. This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). PACS no. 43.55.-n, 43.55.Gx

要旨

本研究は、日本の前近代の最も重要な公共的な公演場所としての代表的な八つの歌舞伎劇場(訳者補注:芝居小屋)を音響調査したものである。ISO3382に従って室内音響の指標について空席状態の劇場を測定し、満席状態をシミュレーションした。ヨーロッパのプロセニアムステージの劇場と比較すると、多くが一層の桟敷席を持つ観客席は天井が低く、可動の舞台背景のための舞台天井は高くない。1席あたりの客席空間の容積は低いために、より短い残響時間となっている。木造で、客席床は布張り椅子ではなく、畳の床でできているため、4kHz帯域までほぼ平坦な特性となっている。その結果、Definition D50(直接音対全エネルギー比)の値や、STI(音声明瞭度指数)の値から音声明瞭度は優良な状態(excerent)が得られている。この様な音響条件が、舞台の前方から客席後方まで伸びた花道(通路)により実現できたダイナミックな演技空間を支えている。これらによって、選ばれた演技の位置に応じて知覚される音響的な親密度に大きなコントラストを与え、観客がドラマティックな演技に没頭できるように支えている。

1.

Introduction

The Kabuki is the most important genre of

traditional Japanese public theater. During the Edo period (1603–1868), it

became the primary form of public entertainment for the growing merchant class

in the urban centers of Japan, with a particular type of performance venue.

Only after the Meiji Restoration of 1868,

characterized by a state driven “modernization through westernization”

affecting all aspects of society, theaters inspired by Western models were

built in major cities such as To¯kyo¯ and Osaka.

At the same time, the industrialization

brought city culture to more rural areas and led to an increase in the

construction of Kabuki theaters outside the cities. Until today, the Kabuki is

a vital form of art, with about 20 active theaters throughout Japan.

1.はじめに

歌舞伎は日本の伝統的な公共的な劇場の最も重要なジャンルである。江戸時代(1603~1868)には特別なタイプの演技空間とともに、成長する商人階級のための公共的な娯楽の初歩的な形が日本の都心にできてきた。1868年の明治維新以降のみ、国家主導の西洋のモデルに社会のあらゆる面で影響を受けた “西洋化を通した近代化”に触発された劇場が、東京や大阪などの主要な都市に建設された。同時に、工業化は都市文化をより地方にもたらし、郊外に歌舞伎劇場(訳者補注:芝居小屋)の建設を増加させた。 今日まで、歌舞伎は重要な芸術形態であり、全国に約20の活動している劇場がある。

The earliest records of Kabuki date back to the beginnings of the Edo period, describing female dance performances accompanied by flutes and drums, which took place on available Shrine stages, as well as on temporary open-air stages in Kyo¯to. These stages were inspired by existing stages for No¯ theater of the time, featuring a roofed stage, while the audience was seated in front of the stage in open air. In 1624 the first permanent theater in Edo (To¯kyo¯ ) was established, called Saruwaka-za (later renamed Nakamura-za). It still had no roof above the audience seats, which were placed in front of the stage (hiradoma).

歌舞伎の最初の記録は江戸時代の初期にさかのぼり、笛と太鼓をバックに女性の踊りが、京都では神社の利用可能な舞台で、また野外の仮設的な舞台などでも行われたと記されている。これらの舞台は、その当時の屋根付きの舞台が有る能舞台に触発されたもので、観客は屋外で舞台の前に座っていた。1624年、江戸(東京)に最初の常設の劇場ができた。猿若座(後に中村座と改名)と言われた。その当時は、舞台の前の場所(平土間)と呼ばれた観客席の上には屋根がなかった。

Permanent roofs started to appear from 1670, but it was only after the issuing of fire regulations in 1723, that tiled roofs were required by the government, which needed new supporting structures. This process was an important step towards the development of the physical theater in its final form [1]. In 1724, the three big theaters in Edo, namely the Nakamura-za, the Ichimura-za, and the Morita-za were all completely equipped with plastered walls and tiled roofs.

恒久的な屋根は1670年から出現し始めたが、瓦ぶきの屋根が政府によって要求されたのは1723年に火災規制が発行されてからであり、その場合には新しい支持構造が必要だった。 このプロセスは、建築的な劇場の最終形態に向けた重要なステップであった【1

賀古論文】。1724年に江戸にある3大劇場、すなわち中村座、市村座、森田座はすべて完全に漆喰の壁と瓦の屋根が装備されていた。

Around the same time, a pathway called hanamichi with about 1.5 m in width, which had started to develop from the end of the 17th century as a temporary extension of the stage, found its final and permanent position at stage right [2, 3]. Starting in 1736, the practice of dividing the pit into rectangular areas of different prices (masu) was introduced. Around 1772 a narrower secondary pathway (kari-hanamachi) was introduced at stage left, and the two were connected by a tertiary path at the back of auditorium (ayumi). Gradually, the theater buildings for Kabuki developed their characteristics distinguishing them from the No¯stage they had originated from. The roof above the stage, typical of the No¯ stage, disappeared from the Kabuki theaters from around 1796. By 1830, the Kabuki theater (or shibai goya as they are usually referred to in Japanese) had reached its mature form [4].

同じころ、花道とよばれる通路、幅がおおよそ1.5mで、仮設の舞台の延長として、17世紀の終わりから発展し始め、舞台の右側の位置(舞台から見て)に最終的な恒久的な位置を見つけた[2,3]。1736年から始まった、客席を四角の形の、値段の異なる席に分割した升席が始まった。1772年ごろ、仮花道とよばれるより細い二番目の花道が、舞台の左側(舞台から見て)に導入された。そして花道、仮花道の両方は観客席の後方の三番目の横通路(あゆみ)(訳者補注:あゆみは花道・仮花道をつなぐ升席の仕切りにもなっている板もあゆみと呼んでいる)で接続された。しだいに歌舞伎のための劇場は能舞台からの特徴を次第に消していった。舞台の上の屋根は、能舞台に特徴的なものだが、1796年ごろ歌舞伎劇場から消えていった。1830年までに、日本では芝居小屋と称された歌舞伎劇場は成熟した形になった[4]。

Kabuki performances present a dramatic plot from a standard repertoire of plays created in the 18th and 19th century. Staging historic events centered around the Samurai class or the life of the commoners of the feudal age, these plays consist of a characteristic form of singing, as well as acting and dancing accompanied by music on and off stage. At the core of a Kabuki performance are the so called mie poses, in which the actor stays in a certain pose at the shichisan point of the hanamichi for a moment to emphasize the action of the plot. These poses, as well as the beginning and the end of a play are accompanied by rhythmical motives, played on woodblocks (ki or tsuke) placed at stage left. A small ensemble of one or more stringed instruments (shamisen), flutes as well as percussion instruments, placed behind a slatted wall on stage right, contribute music and sound effects. Plays can also consist of a narrator sitting on a platform on stage accompanying himself on the shamisen, or passages of acting and dancing without dialog accompanied by a small orchestra of shamisen musicians on stage, which is visible to the audience. The shamisen is plucked with a plectrum and, together with the percussion instruments, forms a rhythmically accentuated background music, while the singers deliver sustained legato notes to it.

歌舞伎の演技は18世紀から19世紀にかけて作られた標準的なレパートリーから劇的な筋書きを提供するようになった。歴史的な出来事の演出は武士階級または封建時代の平民の生活が中心になった。これらの演劇は舞台上または舞台の外で演奏される音楽および歌や演技やダンスを伴っている。歌舞伎演技の中核ではいわゆる見得ポーズが、そこで俳優が花道の7:3ポイントで、あるポーズをして、筋書きの動作を強調する。これらのポーズは演技の始まりや終わりにリズミカルな音を伴って、舞台の左側で置かれた木のブロック(柝(キ)またはツケ)で演奏される。舞台右側(舞台から見て)の黒御簾の裏側におかれた一台または複数の三味線や笛、太鼓などからなるアンサンブルが音楽や効果音に貢献する。演技は舞台の上の演台に座る語りと三味線弾き、または一連の演技や踊りが、小さな三味線の楽団を伴って、観客から見える形で行われる。三味線は撥でひき、と同時に太鼓を伴い、伴奏音としてリズミカルに強調され、歌手は持続的な滑らかな調べを歌う。

In the current study, we present the results of several room acoustical measurement campaigns [5][6], with insitu measurements and room acoustical simulations of a representative sample of remnant Kabuki theaters. The main goal of the study was to describe the range of room acoustical conditions of this performative genre, with a special focus on the particular features of these venues in contrast to theater buildings in the European tradition.

最近の研究で、いくつかの音響的な測定結果を提示する[5][6]。 現在残っている代表的な歌舞伎劇場の音響的な現場測定と音響シミュレーションである。この研究の主の目標はこの演劇的ジャンルの室内音響的な条件を、ヨーロッパの伝統的な劇場と比較して、特別な面に焦点を当てて、述べることである。

2. Description of the theaters劇場の説明

All theaters investigated are two-storey wooden structures. They exhibit the typical architectural features of this building type (Figure 2), and all of thema are still used for performances of traditional Kabuki plays. Two of them, the Ho¯o¯-za and the Kanamaru-za, were built in premodern Japan, during the late Edo period (1603–1868), while six of them were built in the subsequent Meiji period (1868– 1912). Geographically, the theaters are located in three of the four main islands of Japan, including the islands of Shikoku and Kyu¯shu¯ in southern Japan, and Honshu as the largest and most populous island in central Japan.

調査したすべての劇場は2階建ての木造建築物である。それらは図2に示すような典型的は建築的特徴を有し、すべてのテーマは伝統的な歌舞伎劇場の演劇に今でも使われている。そのうちの二つ、鳳凰座と金丸座は近代以前、江戸時代(1603-1868)の後期に建てられている。それ以外の計測した劇場の内、6劇場はそれに続く明治時代(1868-1912)に建設されている。地理的には、劇場は4つの主要な島の3島にある。南の日本の四国および九州および日本の中央部の最も大きく、人口の最も多い本州にある。

The Kanamaru-za, located on the island of Shikoku and completed in 1835, s the Kabuki theaters at the heyday of their development. In terms of size, dimensions, and stage machinery, it matches the dimensions of the three big Edo theaters [7]. The proximity to the Kompira Shrine, considered one of the most sacred places of worship in Japan, seems to be the reason for finding such a remarkable example of Edo period architecture in the rural area of the Kagawa prefecture. The other theater in the island of Shikoku, called the Uchiko-za, located in Uchiko town, Ehime prefecture, was built in 1916, celebrating the coronation of Emperor Taisho [8].

四国に位置し、1835年に完成した金丸座は、歌舞伎発展の最盛期の劇場に似ている。そのサイズ、寸法、舞台機構に関して3大江戸歌舞伎劇場の寸法に一致している[7]。日本で最も神聖な礼拝場所と考えられている金毘羅宮に近いことが、香川県の田園地域にある江戸時代の建物の驚くべき例として考えられる理由と思われる。四国でも愛媛県内子町にある内子座といわれるもう一つの劇場は1916年に大正天皇の戴冠を記念して建設された[8]。

図2 歌舞伎劇場の最も重要な部分のイラスト:通路(花道A)、舞台前の観客席(平土間)

平土間席にはグリッドが設置されている(升B)。両側のボックス席(桟敷席C)、二番目の通路(仮花道)、劇場後方の三番目の平行通路(あゆみE)

Four of the Kabuki theaters investigated are preserved in the Gifu prefecture in central Japan. The Ho¯o¯-za in Gero city is the oldest and also the smallest of the theaters studied. The original date of construction as a nearby shrine stage is unknown (sometime in mid-Edo period) but it was relocated to the current site in 1827 and has been used as a theater since then. The Murakuni-za, opened in 1882 in Kakamigahara city, the Hakuun-za opened in 1890 in Gero city, and the Meiji-za, opened in 1895 in Kashimo village were constructed in the Gifu prefecture in the early years of the Meiji era, when commoners in rural areas of this prefecture came in contact with city culture through the emerging silk industry which resulted in a further development of Kabuki performances and the increased construction of venues for entertainment [9]. The theaters on the island of Kyu¯shu¯ were also constructed in the Meiji era. They include the Yachiyo-za, opened in 1910 in Yamaga city, Kumamoto Prefecture and the Kaho Gekijo, opened in 1921, located in Iizuka city, Fukuoka prefecture. Table I shows the date of opening, the cubic volume, the capacity and the volume per person for the eight theaters considered in this investigation.

調査した4つの歌舞伎劇場は中部日本の岐阜県に残されている。下呂市にある鳳凰座は調査した劇場の中では最も古く、また規模も小さなものである。近くの神社の舞台として建設された日時は不明であるが(江戸時代中頃)、1827年現在の場所に移築され、それ以来劇場として使われている。

各務原市の1882年にオープンした村国座、下呂市に1890年にオープンした白雲座、かしも村に1895年にオープンした明治座は明治時代の初期に岐阜県で建設された。当時農村部の平民が都市文化に新興の絹産業と接触し、その結果歌舞伎公演や娯楽施設の建設が盛んになった[9]。

九州の劇場はやはり明治時代に建設された。八千代座は山鹿市に1910年にオープンした。嘉穂劇場は1921年に飯塚市にオープンした。表1に調査した8つの劇場の開設日、室容積、収容人員、一人当たりの容積を示した。

3. Acoustical investigation 音響調査

3.1. In-situ measurements 現場測定

In the eight theaters of the current study (Table I), room acoustical measurements according to ISO 3382 were carried out [10], using a laptop-based measurement system3 and sine sweeps to obtain impulse responses with a length of 1.6 s for different locations of source and receiver. The dodecahedron loudspeaker (TOA AN-SP1212) was placed at a height of 1.5 m, and the microphones were placed at a height of 0.9 m, considering that the audience was sitting on the floor on tatami mats. Measurements were conducted for two source positions on stage and up to 12 receiver positions, depending on the size of the theater (Figure 4). For two of the theaters (the Meiji-za and the Hakuunza), an exemplary investigation was conducted, comparing the acoustical conditions for the most important acting positions in the Kabuki play. Besides a stage-front and a rear-stage position, which exist also in theaters of the European tradition, these include a particular location on the Hanamichi pathway, where the most crucial parts of a Kabuki play such as the mie poses are presented. This is a point located seven-tenths away from the rear of the auditorium, or three-tenths away from the stage (shichi-san). Thus, in the measurements and simulations of these two venues, three source positions were investigated:

• SA located on the center stage, 0.8 m behind the front of the stage

• SB located on the center stage, 5 m behind the front of the stage

• SC located on the Hanamichi, at the so called shichi-san point

表1の最近調査した8つの劇場では、ISO3382にしたがって行われた室内音響測定laptopのコンピュータのSYSTEM3(訳者注:弊社の音響測定用ソフトDSSF3のこと)のソフトを用いて、SINEスイープ波を用いて、1.6秒間のインパルスレスポンスを異なった音源の位置およびマイクの位置で求めた。12面体スピーカ(TOA AN-SP1212)を1.5mの高さに設置して、マイクは0.9mに設定している。これは畳の床に座ることを考慮してきめた。図4に示すように劇場の大きさにもよるが、舞台上の2つの音源位置と12個の受音点で行われた。二つの劇場(明治座と白雲座)では、見得のような歌舞伎演技の最も重要な演技の位置の音響的な条件を比較するために特別な調査を行った。ヨーロッパの伝統的な劇場で行っている舞台前方および舞台後方の2測点のほかに、花道の特別な場所、歌舞伎の演技の重要な見得の位置も含まれている。この位置は観客席の後ろから10分の7の位置にあり、舞台から10分の3の位置すなわち七三の位置にある。この二つの劇場では測定も音響シミュレーションもこれら3か所の音源位置で調査をした。

•SAは舞台中央、舞台の前面から0.8 m後方にある

•SBは舞台中央、舞台前面から5 m後ろにある。

•SCは、花道の七三と呼ばれる地点にある。

表1 開館年、容積(幾何学的モデルから算出)、収容人員(文献から)、一人当たりの容積

For each source position, 12 receiver positions were measured. Speech transmission index (STI) measurements were carried out using a broadband speaker with a driver of 12 cm diameter. Room acoustical parameters according to ISO 3382 [10] were derived from the impulse responses, including

• the early decay time EDT as a predictor for perceived reverberance,

• the sound strength G as a predictor for perceived loudness,

• the definition D50 (early to total sound energy ratio) as predictor for speech clarity, and

• the early lateral energy fraction JLF as a predictor for perceived source width.

それぞれの音源位置および12の受音点で音声明瞭度指数STIを分析した。スピーカは広帯域の12cmのスピーカ(訳者注 弊社自作)を用いた。室内音響指数はISO3382[10]による室内音響指標はインパルスレスポンスから以下の内容などが導かれる。

•初期残響時間EDT 残響感に対応

•音響重心G:音の大きさに対応

• D50(初期と総音響エネルギー比):音声の明瞭性に対応

•初期の側方のエネルギーJLF :知覚される音源の大きさ。

The parameters derived from the measurements were obtained using a Matlab script based on the ITA toolbox [11]. The parameters derived from the simulations were calculated in the software (see 3.2).

測定によって得られる指数はITAtoolbox[11]に基ずくMatlabによって得られた。音響シミュレーションによって得られた指数は(3.2章)のソフトによって計算された。

3.2. Simulations(音響シミュレーション)

For the acquisition of the geometry of the theaters, three dimensional point cloud data of the Meiji-za, Hakuun-za, Kanamaru-za and Uchiko-za was obtained using a commercially available laser scanner※4. For the other theaters the geometry was determined using a laser distance meter. Based on plan and section cut images exported from the laser scans, as well as on architectural drawings and pictures, computer models were created for the eight theaters, using SketchUp Make 2017.

劇場の幾何学的な形状は3次元の点群データ、明治座、白雲座、金丸座、内子座では市販のレーザースキャナーによって得られた。その他の劇場はレーザー距離計を用いて幾何学的形状を求めた。レーザースキャンによって得られた平面や断面および建築図面や写真に基づいてSketchUp Make 2017を用いて、8つの劇場のモデルが作成された。

※4 Focus 3D S120 Setting 43.7Mpoints / scan.6.136mm / 10m, without color recording,4mins / scan on average レーザースキャナーの仕様

As a general guideline, we have attempted to keep a minimum structural size of 0.5 m in the room acoustical models, which has turned out to deliver the best simulation results [13, p.176], resulting in models with a number of 100 to 300 faces. Scattering coefficients were set as suggested in [14] (a scattering coefficient at 707 Hz is specified and a frequency function of rising scattering values increasing with frequency is extrapolated).

一般的なガイドラインとして、室内音響モデルでは最小構造サイズ0.5mを保つことにした。これにより[13 p.176]の100~300面のモデルがえられ、最高のシミュレーション結果が得られた。散乱係数は[14]で提案された数字にセット出来た。(散乱係数は707Hzで指定され、周波数が大きくなると散乱係数が大きくなる機能が付加されている。)

For the stage and the Hanamichi, absorption coefficients for wooden floor on joists were applied [15], while for the unoccupied and occupied Tatami, absorption coefficients were determined by own measurements (Section 3.3).

舞台および花道のための木製床の吸音率は[15]が適用された。また人が座っている畳と占有していない畳のデータは(Section3.3)著者自身で実測したものである。

The remaining surfaces include different, mostly wooden materials, whose absorption values are quite homogeneous but cannot be specified exactly by measurements in situ. Therefore, a “residual” surface was assigned to all remaining surfaces and the values were fitted so that the resulting room average reverberation time would match the measured results within a JND of 5% as described in ISO 3382. In the model, an omnidirectional source and listeners were inserted at locations corresponding to the microphone positions in the in-situ measurements. The simulations of the speech transmission index (STI) were carried out using the source directivity of a male speaker [16], assuming a normal vocal effort as defined in ANSI 3.5 [17] with a background noise level applying the NC 25 curve. The simulations were further verified by comparing the measured and the simulated STI values, which showed a difference of below 0.05 in all cases. The simulations were conducted using a hybrid mirror image/ray tracing algorithm [18].

残りの部分は、大部分は異なる木製の材料であるが、その吸音率はほとんど一様で、現場では測定によって正確に特定できない。そこで、残りの表面はその他のすべての表面に割り当てられ、ISO3382に述べられているように、JND(Just noticeable difference 丁度可知差異、弁別閾ともいわれる。ISO3382の指標)が5%以内になるように室平均残響時間に一致するように割り当てられる。モデルでは無指向性音源と聴き手の位置は現場測定のマイク位置に一致するように設定されている。音声明瞭度指数(STI)はANSI3.5[17]で述べられている通常の発声を想定した男声の話し手の指向性に合わせた音源を用いて実験をした[16]。暗騒音はNC25曲線に適用できる大きさである。音響シミュレーションはSTIの測定結果とシミュレーション結果を比較してより検証をしている。その結果はすべてのケースで0.05以内の違いに納まっている。この音響シミュレーションは音像法と音線法のハイブリッド計算法で導かれている[18]。

図4 明治座の幾何学的モデルは音響測定とシミュレーションのための音源と受音点の位置を示す。同様のポイントがすべての劇場で設定されている。

3.3. Measurements of absorption coefficients 吸音率の測定

A main difference between the Western theater and the Kabuki theater of Japan is the seating arrangement. The audience is not seated on chairs but on rice straw mats called tatami. Since absorption coefficients of audience seated on Tatami, especially with respect to historical seating density were not available, measurements of the sound absorption according to ISO 354 [19] for unoccupied Tatami as well as for audience sitting on Tatami were carried out in the reverberation chamber of TU Berlin (V = 200 m

3). A test specimen consisting of six Tatami with a total surface area of S = 9.7 m

2was placed on the floor of the chamber (type A mounting). The perimeter of the test specimen was sealed with an acoustically reflective frame made of 30 mm thick wood.

西洋の劇場と歌舞伎劇場の主な違いは、座り方である。観客は椅子に座るのではなく、畳と呼ばれる稲わらのマットに座っている。畳の上に座っている観客の吸音率、特に歴史的な座り方の密度を考慮した吸音率は利用可能なデータがないため、ISO354[19]にしたがって畳の吸音率を人が居ない場合と畳の上に人が座った場合をベルリン工大の残響室(V=200m

3)で実験した。6枚の畳、総合計が9.7m

2の畳の実験材料をタイプAの置き方で実験室の床に置いた。試験体の周辺は厚さ30mmの音響的に反射する材料で覆った。

For the measurements of the absorption coefficient in the occupied case, two Tatami with a total surface area of 3.2 m2 were placed in the corner of the reverberation room. To obtain absorption coefficients of an “infinite surface”, the edges of the test specimen were covered with 500 mm high and 30 mm thick wood panels to avoid the increased aisle absorption, as suggested in [20]. To compensate for the increased sound absorption due to the 3 dB higher sound pressure level in the edges, a correction was applied as suggested by [21], enlarging the test surface by a strip of width b, where b = λm/8.

人が座った場合の吸音率測定のために、2枚の畳、総面積は3.2m2を残響室のコーナーに置いた。無限面の吸音率を得るために、[20]で提案されているように試験体の端を500mmの高さおよび30mmの厚みの木製パネルで覆っている。端で3dB 高いレベルになることで、吸音率が増加することを補正するために、[21]に提案されている補正方法、b=λm/8の幅bで試験体の面積を大きくする方法を適用した。

According to [4], the three Edo theaters in 1841 accommodated five persons in one seating box (Masu), measuring 1.3 m by 1.35 m. In later years, it was tried to increase the capacity of the theaters by reducing the size of one rectangle to 1.2 m by 1.3 m. While the exact size of these rectangles and the number of persons seated there changed over time, seating ten persons on two Tatami (3.2 m

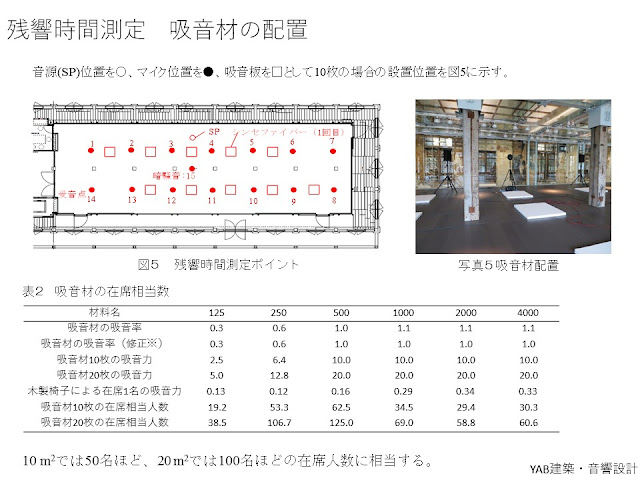

2) seems to be a plausible average of the historical seating density in the Kabuki theaters. Therefore, on two Tatami, ten persons (five male, five female) were seated in three rows of two, three, and two persons resulting in a comparatively tight seating density of approximately three persons per m2. Another factor influencing the sound absorption is the clothing of the audience. Therefore, measurements were performed with persons wearing jackets and persons wearing no jackets. In Figure 5 the sound absorption coefficients αs for Tatami as well as for persons sitting on Tatami with different clothing are shown. The values derived from the measurements were converted to octave band values according to ISO 11654 [22] for the use in the simulations described in Section 3.2.

[4]によれば、1841の3つの江戸の劇場は一つの座るボックス(升席)は、大きさは1.3m×1.35mに5名が収容された。のちには1.2m×1.3mに大きさが小さくなったことで、収容人員を増加させようとした。ところがこれらの実際の四角のサイズと収容人員の関係は時間が経ると変化している、2つの畳に10名が座ることは歌舞伎劇場の歴史的な満席密度のもっともらしい平均と思われる。それゆえ2畳に10名(男5名、女5名)を3列(訳者注:本文中は2名、3名、2名となっているが3名、4名、3名)おおよそ1m

2に3名の密度で座る比較的狭い密度になった。吸音率に影響する他の要因として観客の衣服がある。それゆえ測定はジャケットを着た場合と着ない場合の実験を行った。図5には吸音率は畳の吸音率および異なる衣服を着た場合の人を含む吸音率を示している。測定から得られた値はオクターブバンドにISO11654に従って変換し、3.2章に述べる音響シミュレーションに用いた。

図5 吸音率α

4. Results 結果

4.1. Reverberation times 残響時間

The room average reverberation times values for the unoccupied case derived from the measurements and the occupied case derived from the simulations are shown in Figure 6. For the room averages, the central front stage position and all receiver positions were used. The values for the occupied state are slightly different from a previous publication [23] due to the application of the measured absorption coefficients of Tatami now available.

空席時の測定および満席時の音響シミュレーション時の室平均残響時間を図6に示す。平均は舞台中央の前方のスピーカの位置と12のマイク位置のデータを用いた。満席時の値は最近の論文[23]とは多少異なり、今や可能になった畳の吸音率の測定結果を応用した。

The reverberation times of the unoccupied theaters are in the range of 0.6 to 1.0 s, with the Murakuni-za and the Kaho Gekijo slightly exceeding this range below 500 Hz. The longer reverberation times in the case of the Murakuni-za despite the rather small volume of V = 1195 m2 can be attributed to the fact that this was the only theater within the sample not equipped with a tatami floor as well as to a high ceiling height compared to the floor space. Values for the occupied state are in the range of 0.4 to 0.8 s, with only the Kaho Gekijo, the largest of the theaters measured, exceeding this range with Tm = 1.0 s.

空席の劇場の残響時間は0.6秒から1.0秒の範囲にあり、村国座と嘉穂劇場は500Hz帯域でわずかに超えている。村国座の場合には室容積が1195m3と比較的小さいにもかかわらず長めの残響時間が得られていることは、この劇場は唯一畳が床に設置されていなく、また床面積に比較して天井が高いことが影響している。満席時の値で0.4秒から0.8秒にあるのは嘉穂劇場のみである。この劇場は空席時に1.0秒を超え、もっとも計測した中では大きな劇場である。

The bass ratio (BR) assumes values between 0.9 and 1.3 in the unoccupied condition, rising to between 1.0 and 1.5 in the occupied condition. Towards higher frequencies, the reverberation times of all Kabuki theaters except the Murakuni-za are characterized by an almost flat frequency response up to 4 kHz.

空席状態では低音比は0.9から1.3と満席時1.0から1.5に上昇する。歌舞伎劇場の残響時間は村国座を除きほぼ4kHzまで平坦な特性をもつという特徴がある。

4.2. Early reflections 初期反射音

Individual early reflections, which can make a noticeable contribution to the acoustic characteristics of a room, arrive at the listener for times below the perceptual mixing time, which is between 50 and 100 ms for rooms of this size[24].

個々の初期反射音は、室の音響的特性に顕著に貢献する特性であるが、知覚できるミキシング時間、この大きさの部屋[24]では50~100msであるが、それより前に到達する。

For this time window, Figure 7 shows the typical pattern of early reflections appearing for different positions of the actor on stage, both from measurements in the Hakuun-za theater. With the source located at the center stage position (top), the direct sound is followed by stronger frontal first-order reflections from the floor (1), an upper reflection from the gable roof (3), a lateral reflection from the slanted walls on the side of the stage (4), and a lateral reflection from the sidewalls (5). Another strong reflection arriving approximately 7 ms after the direct sound (2) seems to be a lateral second-order reflection from the side of the Hanamichi and the floor.

この時間窓に対して、図7では典型的な初期反射音のパターンが舞台上の演者の異なる場所で現れることを示している。それらは双方白雲座で計測したものである。上図は音源の位置が舞台中央の位置にある場合で、直接音が床からの強い前方からの一次反射音(1)に続いていること。切妻屋根からの上部方向からの反射音(3)、舞台両サイドの斜めの壁からの側方反射音(4)、そして側壁からの側方反射音(5)。直接音からおおよそ7ms後に到達するその他の強い反射音(2)は花道の片側壁と床から反射する側方の第二次反射音と思われる。

図7 歌舞伎劇場の典型的な反射音のパターン

With the source located at the Hanamichi, strong frontal first order reflections can be identified coming from the floor (1), upper reflections from the two sides of the gable roof (2,3), as well as a late frontal reflection from the back wall of the stage (4).

音源が花道にある場合では、強い前方からの第一次反射音(1)が床から反射してきているのが確認できる。切妻屋根からの上方からの反射音(2,3)、前方からの舞台後壁からの遅れてきた反射音(4)がわかる。

4.3. Room acoustic parameters 室内音響指標

The room average values of the reverberation time T20, the early decay time EDT, the sound strength G, the definition D50 and the speech intelligibility index STI for the unoccupied and the occupied case are shown in Table II.

残響時間T20、初期残響時間EDT、音の強さstrength G、DefinitionD50(直接音対全エネルギー比)、音声明瞭度指数STI 空席の場合と満席時の場合を表2に示す。

表Ⅱ室内音響指数 u:空席、o:満席

Values for D50 between 0.68 and 0.91 and for the STI between 0.63 and 0.74 (both occupied) illustrate the excellent speech intelligibility in all theaters. This is additionally supported by room average values for G between 6.0 and 9.7 dB.

D50の値が0.68と0.91の間で、STIが0.63と0.74(双方満席状態)はすべての劇場で、優れた音声明瞭性を示している。このことはstrengthGが6.0と9.7dBの間にあることでさらに補強されている。

The values for sound strength G at individual listening positions in the eight theaters (occupied) are between 3.4 and 12.9 dB. The decrease with increasing source-receiver distance is shown exemplarily for the Kaho Gekijo theater (Figure 8), with simulated values for the occupied condition compared to predictions by the classical diffuse field theory and Barrons’s revised theory [29, 30]. Although the revised theory systematically overestimates the simulated values by about 1 dB, it offers a consistently better fit than the classical theory, also in all other theaters considered.

8つの劇場(満席状態)の個々の観客の聴取位置のstrengthGの大きさは3.4と12.9の間にある。音源―聴き手の距離が大きくなってくるとその値は減少することを嘉穂劇場(図8)で示されている。満席時の音響シミュレーション結果は、古典的な拡散理論およびBarronの改良理論[29,30]によって予測される値を比較して示す。改良理論はシミュレーション結果を約1dB どの位置でも大きめに出ているが、古典理論より一貫してよりよく評価できる。このことはその他の劇場のことを考慮しても成り立つ。

The values for early lateral energy fraction

JLF, calculated for the Meiji-za and the Hakuun-za theater (Table III) are similar to those reported for 19th century theaters in Vienna such as the old Burgtheater (JLF = 0.15), the Kärntnertortheater (JLF = 0.25) and the Theater an der Wien (JLF = 0.25) [27].

初期側方エネルギー率(JLF)の値、明治座と白雲座(表3)に示すように計算され、ウイーンの19世紀の古いブルグ劇場(JFL=0.15)、ケルントナー劇場(JFL=0.25)、アンデアウイーン劇場(JFL=0.25)[27]と似たような値となっている。

表Ⅲ ISO3382の指数比較(満席時)

4.4. Room acoustics and acting position 室内音響と演技位置

In contrast to the classical European proscenium stage the Kabuki theatre allows actors to take up different positions in front of, inside and behind the audience. By the example of two theatres (Meiji-za and Hakuun-za), Table III and Figure 9 illustrate the acoustic effect of the different acting positions (main stage front, main stage back, Hanamichi pathway). With Speech Transmission Indices STI ≥ 0.65 and D50,m values ≥ 0.73, speech intelligibility is always good regardless of the source location in both theaters. Nevertheless, there is a notable increase of both loudness (Gm), intelligibility (STI) and direct-to-diffuse ratio (as characterized by D50) with the speaker moving from stage back to stage front to the Hanamichi position. The big difference between the stage back and stage front positions is due to the absence of a stage canopy, which is why the rear position is only supported by a weak ceiling reflection at the lower edge of the stage portal. As the most important acoustical cues for the perceived distance, these differences between the acting positions entail notable different sensations of proximity between actors and audience.

古典的なヨーロッパのプロセニアム舞台と比較して、歌舞伎劇場では俳優は観客席の様々な位置、前方や両側や後方の様々な位置を選ぶことができる。明治座および白雲座の二つの劇場例では、表3および図9は演技の位置(主舞台前方、主舞台後方、花道)に対する異なる音響効果を示している。音声明瞭度指数STIは0.65以上、D50mは0.73以上あり、音声明瞭性は両劇場とも音源の位置にかかわらずGOODを示している。話し手が舞台後方から、舞台前方に移動し、さらに花道の位置に移動しても、ラウドネスGm、明瞭度指数STIと直接音対間接音(D50で表される)の著しい増加がみられる。舞台後方と舞台前方との大きな違いは舞台上部の屋根(からの反射音)がないことによる。このことで舞台後方の位置は舞台の額縁の低い位置によって、弱い天井の反射音しか得られないからである。知覚距離の最も重要な音響的な手掛かりとして、演技者の位置の違いが、演者と観客の間に親密感の著しい違いをもたらす。

As an example, the spatial distribution of STI values for the three source locations (Figure 9) illustrates how different parts of the audience are addressed by different positions of the actors and how the sensation of being within the dramatic action evolves, when taking into consideration that the actors can freely move between these points, and that several actors can be positioned at different locations at the same time.

一例として、3つの音源位置のSTI値の空間分布(図9)は、さまざまなところにいる観客が俳優の異なる位置によって影響を受け、俳優は自由にこれらの位置に移動し、何人かの俳優が同時に別の位置に移動することで劇的な演技が得られることを示している。

図9 シミュレーションによるSTI(上段:花道、中段:舞台後方、下段:舞台前方

4.5. Original Data 原データ

The original CAD-Models (.skp) of the eight theaters, including the source and receiver positions used in the measurements and simulations are available as an electronic publication [28].

8つの劇場の原CADモデル(.skp)、測定とシミュレーションで使用したソースとレシーバーの位置を含むデータは、電子出版物として入手できる[28]。

5. Discussion 考察

The Kabuki as the most important traditional Japanese public theater form with its characteristic mixture of spoken and sung vocal passages with instrumental accompaniment has brought forth also a particular architectural type of performance venue. It is a usually two-storey building with a rectangular floor plan, and with the audience sitting on Tatami mats on the floor and on one surrounding gallery. Measurements and simulations of a representative sample of eight Kabuki theaters built between 1827 and 1921 (late Edo, Meiji and Taisho period) indicate the characteristic acoustical conditions of this genre. In comparison with European proscenium stage theaters such as the Viennese court theatres or the small Italian opera houses of the same epoch (Figure 10, [25, 27]), the Kabuki theaters are less reverberant relative to their size due to the relatively small volume per seat of 1–4 m

3, except of one venue which is slightly larger. Although Kabuki plays combine elements of song, pantomime and dance with instrumental accompaniment, the acoustical conditions consistently seem to be designed for optimal speech intelligibility, which is indicated by early to late energy ratios (D50,m) above 0.68 and speech transmission indices (STI) above 0.63 in the occupied condition, as well as a rather flat frequency-dependent reverberation time for all theaters of the sample up to 4 kHz. The conditions in terms of size and reverberation are most comparable with those of English theatres from this period such as Theatre Royal in Bristol or Wyndham’s Theatre in London [26].

最も重要な伝統的な日本の公共劇場形式の歌舞伎は、器楽を伴った話声や歌が混ざった演技が特徴であり、演技空間の特別な建築の型式をもたらした。通常は2階建て、四角い平面で、観客は平土間か周囲の桟敷席(ギャラリー)の畳の上に座る。

音響測定とシミュレーションは、1827年と1921年の間(江戸後期、、明治期、大正期)にできた代表的な8つの劇場において、この伝統的な分野での音響的な特徴を示している。ヨーロッパのプロセニアム舞台タイプの劇場、たとえばウイーンの宮廷劇場または同時代の小さなイタリアのオペラハウス(図10、[25,27])と比較すると、歌舞伎劇場は相対的に1席当たりの容積も1~4m

3と小さいために、少し大きな劇場(訳者注:村国座)を除いて、歌舞伎劇場は比較的残響が短い。歌舞伎は器楽演奏を伴った歌や言葉の無い演技や舞踊を演じるにもかかわらず、音響条件は一貫して最適な音声明瞭性をデザインしている。それは初期音―残響音のエネルギー比(D50,m)が0.68以上、音声明瞭度指数STIは満席で0.63以上、どちらかといえば調査した劇場すべてが4kHz帯域まで残響時間が平坦な周波数特性となっている。大きさや残響時間の条件ではBristolのロイヤル劇場やロンドンのWyndham劇場[26]のような同時代のイギリスの劇場が最も比較できる。

One main difference when comparing the Kabuki theater to most stages in European tradition is "the unlimited freedom of its theatrical space where stage and auditorium merge and actor and audience sympathetically fuse into one" [7, p. 49]. This is achieved by an extension of the main stage by three pathways surrounding the audience, with the Hanamichi (stage-right) as the most important. Together with the seating arrangement, which does, unlike European proscenium theaters, not predetermine the spectators’ viewing direction, this creates a dynamic performance space and a high degree of immersion into the dramatic action with respect to the social, visual and acoustical experience, as illustrated both by the overall change in room acoustical conditions and the spatial distribution of room acoustical parameters such as the speech transmission index (STI) for the different acting positions.

歌舞伎劇場とヨーロッパの伝統的な劇場の一つの主な違いは『舞台と観客席が合体し、俳優と観客が共感して一つに融合する劇場空間の無限の自由』があること [7、p.49] 。このことは主舞台の延長としての3つの通路、なかでも最も重要な花道(舞台右側)によって成し遂げられている。ヨーロッパのプロセニアム劇場と異なり、椅子の配置に伴って、観客の視線があらかじめ決められていない。このことによって劇的な演出と社会的、視覚的、音響的な体験を伴うドラマティックな演出に高度な一体感が生まれる。それらは室内音響条件の全体的な変化と、演技位置が異なる場合の音声明瞭度指数(STI)などの室内音響指数の空間分布の両方によって示される。

These acoustic conditions characterize not only the experience of the audience of a theatrical genre of particular importance for Japanese culture, with its peculiar mixture of spoken theatre and music; they also characterize the cultural experience of a Japanese audience with the room acoustic conditions of music and theater performances in general, at a time when Western concert culture came to Japan after the opening of the country following the Meiji Restoration of 1868. In contrast to a European audience whose experience was shaped by a variety of performance venues including large and reverberant spaces such as churches, large baroque festival halls, or even by Renaissance music theater in rooms with 2–3 s reverberation [32], the Japanese audience only knew open-air performances, such as the older No¯ Theater, and the conditions of the Kabuki theater represented by the sample of rooms described here, with a densely packed audience and very clear acoustics. Western room acoustic standards for musical concerts with a reverberation time of about 2 s were thus highly unusual for a Japanese audience and could establish themselves only with a great delay in the second half of the 20th century [33].

これらの音響条件は、演劇と音楽の独特の混合により、日本文化にとって特に重要な劇場分野の聴衆の体験を特徴付けるだけではなく、概して音楽や演劇の室内音響条件に伴って日本人の観客の文化的な経験を特徴づけている。と同時に、ヨーロッパのコンサート文化が1868年の明治維新に伴って開国したのちに入ってきた。ヨーロッパの観客、彼らの経験は大きなまた残響の長い場所、すなわち教会や大きなバロックの祝祭劇場、または残響時間が2-3秒あるルネッサンス音楽劇場を含む場所で経験を積んできたヨーロッパの観客と比較して、日本の観客は野外公演、例えばより古い能舞台、ここで述べた代表的な歌舞伎劇場の条件でしか経験がなかった。観客は密集して座り、大変明瞭な音響状態が条件であった。西洋の音楽コンサートの室内音響の残響時間が約2秒の標準は、日本人の観客にとって非常に珍しく、非常に遅れて20世紀の後半に確立することができた[33]。

Acknowledgements

The project was supported by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, WE 4057/12- 1). The authors would like to thank Norio Nakashima, CEO of Nakashima Corporation for organizing the necessary contact to make this survey possible, as well as the Japanisch-Deutsches Zentrum Berlin for supplying the Tatami used in the reverberation chamber measurements.

謝辞

このプロジェクトは、ドイツの研究財団(Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft、WE 4057 / 12-1)に援助を受けた。 著者は、この調査を可能にするために必要な連絡を取りまとめてくれた中島コーポレーションのCEO中島典夫氏と、残響室の測定に使用される畳を提供してくれたベルリン日本中央研究所に感謝する。

References

[1] T. Kako: Karigake no yane; Kenchiku k¯oso kara mita shibaigoya ¯oyane no hattatsu [Temporal roof, Development of main roof seen from the point of architectural conception].

Theater and Film Studies, Waseda University 2 (2009) 135–164.

[2] T. Kawatake: The Kabuki theater, 2: The hanamichi. Japan Architect 37, 10 (1962) 94–99.

[3] H. Suwa: The birth of the hanamichi. Theatre Research International 24, 1 (1999) 24–41.

[4] E. Ernst: The Kabuki theatre. University Press of Hawaii, Honolulu, 1974.

[5] M. Yabushita, M. Terao, and H. Sekine: Mokuz¯o shibaigoya no onky¯o tokusei: 2. [The acoustical characteristics of wooden playhouses, 2] Proc. of the Architectural Institute of Japan (2009) 331–332.

[6] M. Yabushita, M. Terao, and H. Sekine: Mokuz¯o shibaigoya no onky¯o tokusei: 3. [The acoustical characteristics

of wooden playhouses, 2] AIJ Journal of Technology and Design 18, 38 (2012) 229–232.

[7] T. Kawatake: Kabuki: Baroque fusion of the arts. The International House of Japan, Tokyo, 2003.

[8] Uchiko-za hensh¯u iinkai, ed.: Uchiko-za: Chiiki ga sasaeru machi no gekijo no 100 nen [Uchiko-za, 100 years of town theater supported by the regional community]. Gakugei shuppansha, Kyoto, 2016.

[9] K. Got¯o: Chiiki shakai ni okeru keizai hatten to bunka keisei:Meiji shoki no gifu ken t¯on¯o chiho no gekij¯o gata n¯oson butai wo sozai toshite [Economic development and the formation of a cultural infrastructure in the regional society:The regional theaters in east gifu prefecture in the late nineteenth century]. The Economic Review 11 (1996) 5–18.

[10] ISO 3382-1:2009: Acoustics – Measurement of room acoustic parameters, Part 1: Performance spaces.

[11] P. Dietrich, M. Guski, J. Klein, M. Müller-Trapet, M. Pollow,R. Scharrer, M. Vorländer:

Measurements and Room Acoustic Analysis with the ITA-Toolbox for MATLAB. 40th Italian (AIA) Annual Conference on Acoustics and the 39th German Annual Conference on Acoustics (DAGA).2013.

[12] ISO 18233:2006: Acoustics – Application of new measurement methods in building and room acoustics.

[13] M. Vorländer: Auralization: Fundamentals of acoustics,modelling, simulation, algorithms and acoustic virtual reality. Springer, Berlin, 2008.

[14] Odeon A/S: Scion DTU, Diplomvej, building 381, DK-2800 Kgs. Lyngby, ODEON Room Acoustics Software, 7,2016.

[15] W. Fasold and E. Veres: Schallschutz und Raumakustik in der Praxis: Planungsbeispiele und konstruktive Lösungen. Huss-Medien, Berlin, 2003.

[16] W. T. Chu, A. C. C.Warnock: Detailed Directivity of Sound Fields Around Human Talkers. IRC-RR 104. National Research Council. Canada, 2002.

[17] ANSI 3.5-1997: Methods for calculation of the speech intelligibility index.

[18] J. Rindel: The use of computer modelling in room acoustics.Journal of Vibroengineering 3 (2000) 219–224.

[19] ISO 354:2003: Acoustics – Measurement of sound absorption in a reverberation room.

[20] U. Kath, W. Kuhl: Messungen zur Schallabsorption von Polsterstühlen mit und ohne Personen. Acta Acust united Ac 15 (1965) 128–131.

[21] U. Kath, W. Kuhl: Messungen zur Schallabsorption von Personen auf ungepolsterten Stühlen. Acta Acust united Ac 14 (1964) 50–65.

[22] ISO 11654:1997: Acoustics – Sound absorbers for use in buildings, Rating of sound absorption.

[23] C. Büttner, S. Weinzierl, M. Yabushita, Y. Yasuda: Acoustical characteristics of preserved wooden style kabuki theaters in Japan. Proc. of the EAA Forum Acusticum 2014,Krakow, 629–630.

[24] A. Lindau, L. Kosanke, S.Weinzierl: Perceptual evaluation of model- and signal-based predictors of the mixing time in binaural room impulse responses. J. Audio Eng. Soc. 60 (2012) 887–898.

[25] D. D’Orazio, S. Nannini: Towards Italian Opera Houses: A Review of Acoustic Design in Pre-Sabine Scholars. Acoustics 1 (2019) 252–280.

[26] M. Barron: Auditorium acoustics and architectural design. Spon Press, London, 2010.

[27] S. Weinzierl: Beethovens Konzerträume: Raumakustik und symphonische Aufführungspraxis an der Schwelle zum modernen Konzertwesen. E. Bochinsky, Frankfurt am Main, 2002.

[28] C. Büttner, M. Yabushita, A. Sanchez Parecho, Y. Morishita, S. Weinzierl: The Acoustics of Kabuki Theaters –

Input Data for Room Acoustic Simulations.

http://dx.doi. org/10.14279/depositonce-7243.

[29] J. S. Bradley: A comparison of three classical concert halls.J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 89 (1991) 1176–1192.

[30] M. Barron, L.-.J Lee: Energy relations in concert auditoriums.I. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 84 (1988) 618–628.

[31] M. Garai, S. Cesaris, F. Morandi, D. D’Orazio: Sound energy distribution in Italian opera houses. Proceedings of the 22nd International Congress on Acoustics 2016. Buenos Aires.

[32] S.Weinzierl, P. Sanvito, F. Schultz, C. Büttner: The Acoustics of Renaissance Theatres in Italy. Acta Acust united Ac 101 (2015) 632–641.

[33] T. Mikami: Zanky¯o 2 by¯o; Sa Shinufonih¯oru no tanj¯o. [Two seconds reverberation. The birth of the Symphony Hall] Osaka Shoseki. Osaka. 1983.